Premise

This blog post contains the full text of my Master Thesis, written at the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen and at the University of Pavia and submitted for the first time during February 2023.

The research question investigates which characteristic out of reputation, popularity and developer’s brand, reflected in some elements in the presentation page on app stores, is the most effective in predicting user’s choice to download an app.

First, Chapter 1 provides an extensive background on the mobile ecosystem, its participants and its dynamics. Then, in Chapter 2, the previous literature results on the effects of those factors are covered, while, finally, in Chapter 3 and 4 the empirical analysis and its results and discussion are presented.

The full document version of this thesis is available here, while a summary presentation can be found here.

Abstract

After providing an extensive background on the mobile ecosystem, its participants and its dynamics, this research aims to establish which characteristic out of reputation, popularity and developer’s brand, reflected in some elements in the presentation page on app stores, is the most effective in predicting user’s choice to download an app. Experimental results show how developer’s brand is generally the most decisive element, but, when comparison between apps is introduced in the model, it loses its effectiveness and reputation becomes more relevant. Popularity and peer influence, in the context of low network effects, appear to be unexpectedly ineffective in driving users’ decisions across all models. Moreover, users’ involvement in the download process reinforces the effect of reputation, while, when customers are more involved in the specific app category and perceive a higher risk, apps from established brands are more likely to benefit. Finally, it was not possible to find clear evidence of any two-way interaction between reputation, popularity and brand.

(in Italian)

Dopo aver fornito una descrizione dell’ecosistema mobile, dei suoi partecipanti e delle sue dinamiche, questa ricerca si pone l’obiettivo di stabilire quale caratteristica tra la reputazione, la popolarità e il brand dello sviluppatore, riflesse in alcuni elementi nella pagina di presentazione sugli app store, sia la più efficace nel predirre la scelta dell’utente di scaricare un’applicazione mobile rispetto ad un’altra. I risultati dell’esperimento mostrano come il brand dello sviluppatore è generalmente il fattore più influente. Tuttavia, quando la possibilità di comparare le applicazioni è introdotta nel modello, il brand perde parte della sua efficacia e la reputazione diventa più rilevante. La popolarità dell’applicazione tra gli altri utenti, in un contesto di scarsi effetti di rete, sembra essere sorprendentemente inefficace nell’influenzare le scelte degli utenti in tutti i modelli. In aggiunta, il coinvolgimento dell’utente nel processo di download delle applicazioni rinforza l’effetto della reputazione, mentre, quando l’utente è più coinvolto nella specifica categoria di applicazioni e quindi percepisce un rischio maggiore, le applicazioni sviluppate da brand consolidati hanno più probabilità di essere scelte. Infine, non è stato possibile individuare alcuna interazione bidirezionale significante tra reputazione, popolarità e brand dello sviluppatore.

Chapter 1. Introduction

The mobile industry has incredibly changed throughout the years it existed. While the developments in hardware and software components have been in the public eye for many years now, the most impressive change was arguably the shift in power and influence among market participants.

In fact, the industry’s balance of power, which back in the 1990s and early 2000s used to favour mobile device manufacturers and, in particular, network operators, now sees a hardly disputed winner, which are mobile platform providers, like Google or Apple (Basole et. Karla, 2012, p. 35).

The most important year in this transition was 2008 and Apple was probably the main actor. As commonly known, in 2007, Apple launched the first version of the iPhone and it could be argued that the real innovation didn’t lay in the new hardware features of this phone: Apple’s iPhone wasn’t the first one to introduce a capacitive touchscreen, for example, and LG did that some time in advance in 2006 (Ihlwan, 2007). The real breakthrough that initiated the “app economy” was the introduction, in 2008, of Apple’s App Store, a mobile application marketplace with originally a few more than 500 apps and which now accounts for more than 1.5 million applications (Basole and Karla, 2012, p. 32; Ceci, 2022b; Friedman, 2013). The first app stores were launched at the end of the 1990s, but it wasn’t until almost a decade later, with the Apple Store, that they started to gain traction (Kouris and Piller, 2014, p. 21). Since then, the increasing availability of mobile apps, supported by enhancements in hardware features, drove the growth of the mobile industry. In fact, the number of smartphone users worldwide almost duplicated only considering the last five-year period, reaching 6.2 billion users in 2021 and being expected to grow up to 7.6 billion in 2027 (Ericsson, 2022). Meanwhile, apps became an incredibly profitable business by themselves and those downloaded from the Google Play Store, the largest app store by the number of available apps at the moment (3.5 million apps in 2022), generated in 2021 more than $ 47 billion in gross revenue, three times more than what was generated back in 2016 (Ceci, 2022a, 2022b).

Clearly, being the owner of a successful app marketplace is a position as desirable as difficult to reach for companies operating in the mobile ecosystem and many appear to fail while attempting that. The complex dynamics lying behind the interaction among market participants (e.g. app developers and customers) are shaped by the mechanics of information economics, which may raise entry barriers and uncertainty. While past literature has already provided useful insights on two-sided platforms,1 a category to which app marketplaces belong, some elements of customer behaviour, when dealing with digital products, need to be explored more deeply. However, before investigating users’ preferences on mobile app stores and focusing on empirical evidence, an overview of the mobile ecosystem is necessary.

1.1 Mobile Ecosystem

The mobile phone industry is now more than forty years old. In 1978, in fact, a Motorola engineer, Martin Cooper, who is today considered the inventor of the cell phone, made the first mobile phone call using a Motorola DynaTac in New York (Zheng and Ni, 2010, p. 32). Six years later, in 1984, a more recent version of the same Motorola phone was commercialized for the first time. Those phones were also defined as “brick phones”, due to their shape and size, and, in the following ten or twenty years, the innovation efforts of this industry focused on miniaturization, better power efficiency and battery life, better displays and signal. In the meantime, generations of cellular network technologies were succeeding (from 1G to today’s 5G), improving voice communication quality, as well as introducing revolutionary features such as text messaging or Internet access. However, the real disruption in this industry came in 2008, with the introduction of the first smartphones and of the app concept, which overturned power relations between market participants.

Basole and Karla (2012, p. 28) identified four groups of market participants, mobile platform providers, mobile device manufacturers, mobile network operators, and mobile application providers, to which a fifth group, mobile users, can be added to effectively understand the industry’s internal dynamics.

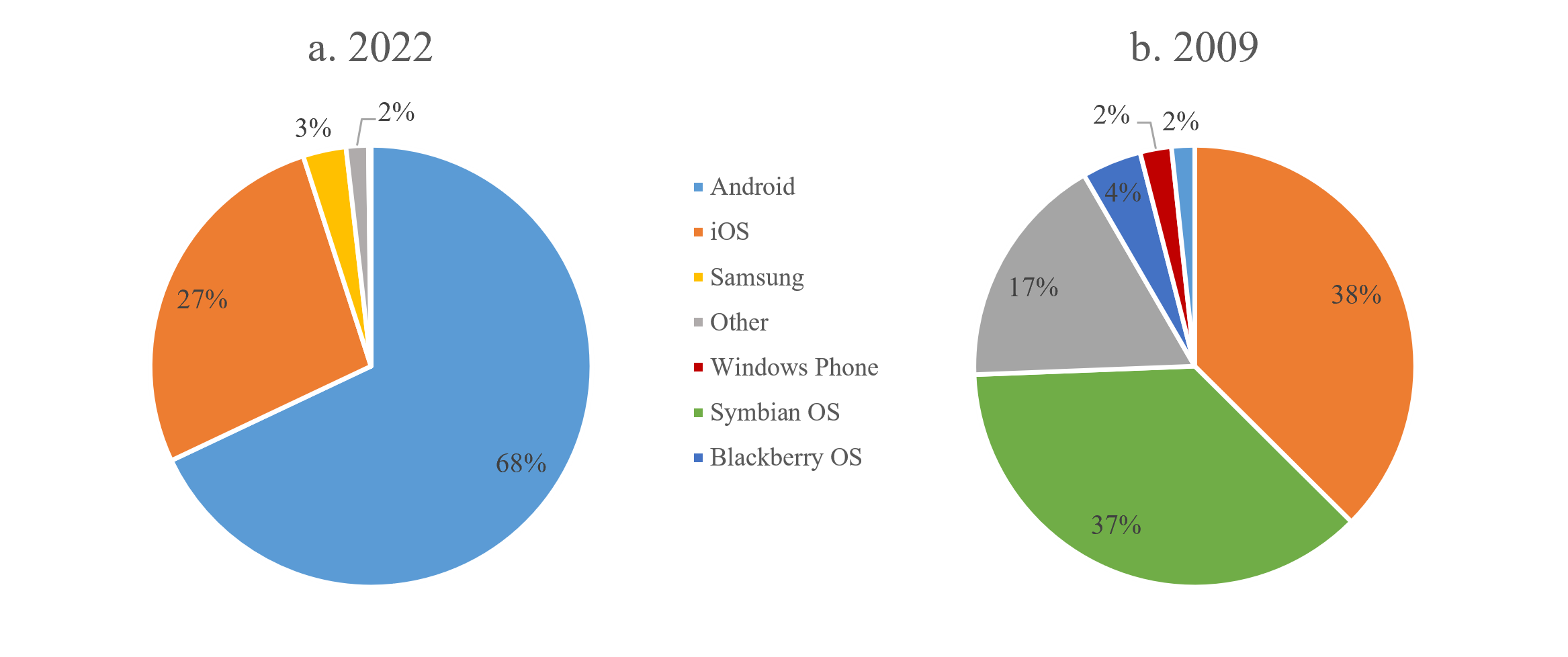

Mobile Platform Providers. Mobile platform providers (MPPs) provide operating systems and middleware solutions for smartphones and they are currently driving the mobile industry. In addition, MPPs often coincide with the owners of major mobile app stores. This double role was arguably assumed for the first time by Apple in 2008, when, while launching the iPhone, it leveraged its experience in content distribution, thanks to the previous existence of iTunes, to introduce the App Store, in order to strengthen its ecosystem and drive demand for iOS devices (Basole and Karla, 2012, p. 36; Cortimiglia et al., 2011, p. 3), before app stores became a profitable business by their own. While a couple of years after its introduction, iOS was installed on 37 percent of all smartphones, a market share similar to the one of Symbian OS (Nokia’s own operative system), and Android had just entered the market, as shown in Fig. 1.1, now the latter dominates other mobile operative systems (with about 71 percent of the global market), just followed by iOS and other operative systems with very small shares (Laricchia, 2022).

Figure 1.1: Mobile OS market shares in 2022 and 2009 (Laricchia, 2022).

Interestingly, these two systems were both able to succeed with two different approaches: iOS is considered a relatively closed ecosystem (“walled garden”), while Android is a more open one (“open garden”). The unique role of Apple as both MPP and device manufacturer enables it to apply some restrictions, as, for example, the fact that apps can only be installed from the App Store, as sole source (Basole and Karla, 2012, p.36; Cortimiglia et al., 2011, p. 3), and this approach allows more strict testing and verification, that, in combination with the existence of only a few different hardware with that operative system (OS), may lead to a better user experience, with consequently improved customer loyalty and a premium brand image. On the other hand, Android is an open-source OS and the ecosystem is more open: this may lead to higher levels of competition both on software and hardware, with lower prices as result (Müller et al., 2011, p. 74). In terms of app distribution, both Apple and Google act as gatekeepers: they decide what gets published on their stores, also covering important roles in terms of quality assurance and pre-screening of dangerous apps (Müller et al., 2011, p. 73), but, while in Google case, these limits can be circumvented thanks to the presence of other app sources, this is (legally, at least) impossible on Apple’s devices.

Overall, MPPs took over many parts of the value chain, from OS development to payment systems, relegating other participants to more subordinate roles.

Mobile Device Manufacturers. Mobile device manufacturers’ (MDMs) activity mainly consists in producing and distributing the hardware part of a smartphone. In the past, MDMs generally owned proprietary operative systems installed on their products, only a few native apps were offered with the phone and the possibility of installing third-party apps was generally limited. Their role was strictly connected to the one of network operators, on which they often depended for distributing devices, usually sold in combination with mobile subscriptions (Basole and Karla, 2012, p. 29).

Today, the only MDMs developing a popular OS are the most important MPPs, Apple and Google, while all the other producers (Samsung, Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo, etc.) redirected themselves towards Android as the chosen OS for their devices in most cases.

Mobile Network Operators. Mobile network operators (MNOs) have been dominant in the mobile service industry for many years. For decades, they were the main sources of innovation and added value, they supplied SIM cards and they could also dictate some pre-settings, like the browser’s homepage or types of applications installed (Basole and Karla, 2012, p. 29). Later, with the smartphone introduction and the app economy emerging, MNOs lost their traditionally central role, their margins shrunk and the risk of becoming dumb pipes is real.

Mobile Application Providers. Mobile application providers (MAPs) are those providing content in the current mobile ecosystem. They develop both web-based and native applications for specific technology platforms, which cover many different categories and use cases. Developers traditionally lacked market accessibility and app stores greatly reduced barriers and time-to-market for them, but, on the other side, they now largely depend on MPPs’ enabling capabilities and developing tools (Basole and Karla, 2012, p. 30). Anyway, MAPs can now reach a large number of potential customers, at the price of leaving (on average) 30 percent of their app download revenue to gatekeepers (Cortimiglia et al., 2011, p. 5), whose role is particularly restricting in walled gardens, due to the lack of alternative channels.

Mobile Users. On the other side of a mobile app store, there are smartphone users. They search, download and pay for apps and they also later rate them. There is a tendency among users to view the mobile device and available apps as a package: they take into consideration the ecosystem as a whole and then decide which hardware and software combination to buy. In this sense, mobile devices can be considered complementary goods for apps and their price a one-time membership fee to join the ecosystem (Kouris and Piller, 2014, p. 36).

For customers, downloading an app and the perception of the risk involved depend more on the MPPs than MAPs: users, in fact, place their trust in platform owners as their main source of information. In addition, they use apps to perform highly fragmented everyday tasks and perceive apps not as complex as traditional desktop software. This makes their buying decision limited, habitual and impulsive, corresponding to generally low levels of involvement (Buck et al., 2014, p. 5). During the download process, users often don’t search for information actively and reputation systems (e.g. rating score), as well as peer influence (e.g. sale rankings, number of downloads), drive their decision-making (Buck et al., 2014, p. 5; Liu et al., 2014, p. 330).

1.2 Mobile Apps as Digital Products

The term “mobile application”, “mobile app” or just “app” refers to application software, which is “a type of software that allows the user to perform a specific task, that can be installed and run on a range of portable devices such as smartphones and tablets” (Liu et al., 2014, p. 327). An app usually distinguishes itself by general software because it is optimized for touch-screen-based mobile devices, it is offered free of charge or for sale and the most of the times it is available for download through a centralized online marketplace where users can also rate and review the app and access some ranking lists (Liu et al., 2014, p. 327). Apps already have a longer history than one could expect: for example, Zheng and Ni (2010, pp. 51-56) were able to individuate two generations of mobile apps already back in 2010. The first generation involved very simple apps, such as ringtones, instant messaging and personal information management apps, among which the first one was the most popular for many years. Then, the second generation included more complex apps like mobile commerce, gaming, music streaming and mobile social networking and some of these are still popular today. Later, a third generation emerged, with features like augmented reality, ubiquitous social networks and merging and seamless switching between different functions (Kouris and Piller, 2014, p. 25).

Mobile apps, exactly like all types of software, are digital goods and as such they share all the typical characteristics of this category of products. Compared to standard economic models, in a digital information setting, costs fall substantially and approach zero. In fact, Goldfarb and Tucker (2019, p. 3) were able to identify five types of cost reduction: lower search costs, lower replication costs, lower transportation costs, lower tracking costs and lower verification costs. Even if these cost reductions are intrinsic to all digital (i.e. intangible) goods and services, they are enhanced by the use of mobile app stores as the main distribution channel.

In fact, mobile app stores are an example of two-sided platforms. These platforms are intermediaries that enable exchanges between other players and, by doing that, they efficiently organize supply and demand allowing buyers to access the sellers (and vice versa), facilitating matchmaking and lowering transaction costs. Platforms aggregate information and provide access to that data to market participants and also provide ratings and feedbacks that help to build credibility and trust among participants, making some previously unknown seller characteristics observable, rewarding the better-quality users and creating incentives for lower-quality ones to leave the market. In exchange for easier transactions, these businesses charge a share of their value for the service (Lambrecht et al., 2014, p. 10). In addition, by aggregating market participants, intermediary platforms generate indirect externalities (or indirect network effects): in fact, they usually consist of two-sided (or multi-sided) networks with two (or multiple) types of members, where each type is looking for a network with the largest number of users of the other type. In these cases, network effects become so strong that customers tend to pick a network, instead of choosing a service or a product, since the utility on one side of the market highly depends on the number and quality of participants on the other side (Kouris and Piller, 2014, pp. 39-40; Piccoli and Pigni, 2019, p. 239). Indeed, mobile app stores are characterized by a positive feedback loop: the greater the number of users of the store (reflected in the number of downloaded apps or in the installed subscriber base), the more attractive that marketplace becomes for developers, resulting in an increase of the supply of content and applications and, as a consequence, in higher consumer benefits and increased attractiveness for additional users (Basole and Karla, 2012, p. 35).

Lower Search Costs. It is a lot easier to find and compare information about potential transactions online than it is offline. As a consequence of the decrease in search costs, prices have fallen and product variety increased (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2019, pp. 6-7). While prices online appear to be constantly lower than offline, also for tangible products (e.g. Brynjolfsson and Smith, 2000, p. 579), in purely digital contexts, such as app marketplaces, prices actually reached zero in many cases. Minimal search costs, together with other reasons that will be later discussed, had an important role in spreading and making successful the freemium strategy and increasing the offer of free apps.

However, even if prices are lower, an important level of price dispersion persists online. The ease of changing prices and running price promotions on mobile apps, which also have no marginal costs of production, makes this a common characteristic of mobile app stores too. “Free App of the Day” promotions are an example of an initiative that could rise price dispersion on app marketplaces. This kind of initiative involves spotlighting in the homepage and zero-pricing an app for 24 hours and it had been used in the past, for some periods, by the Google Play Store, the Apple App Store and the Amazon Appstore, the three most popular app stores today (Chen et al., 2022, pp. 1-2). The objective of this practice is combining digital free sampling, which proved to be effective in reaching new customers, with sponsorship practices, like featuring the app in a noticeable position, consequently increasing visibility and enhancing customer awareness of the app. According to Chen et al. (2022, pp. 6-7), such a promotion may lead to adverse effects in the post-promotion phase: firstly, the removal of zero-price hurts sales, in particular, due to customers’ expectations of the app being free and their perception of a loss by observing the restored (and increased) price; secondly, promotion-induced reviews, generated by the increased visibility of the app, are less effective than organic ones.

Low search costs also mean that it is way easier to find rare and niche products online (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2019, p. 8), a phenomenon defined by Anderson (2006, p. 22) as “the long tail”. The effects of the long tail are particularly visible on app stores: apps generally require just relatively little storage space, making welcoming as many apps as possible quite inexpensive for marketplace owners, with positive benefits overall. Regardless of the number of sales, unsuccessful apps provide additional choices and options for customers, reinforcing the two-sided positive feedback loop (Basole and Karla, 2012, p. 35). In addition, the growing user-friendliness of developing tools allowed many people besides professional developers to publish their apps, further increasing the range of available options. A broader choice of apps, from a negative perspective, leads to higher choice complexity, which could cause delays in the users’ app download process. This negative effect of the long tail is usually mitigated by recommendation systems, app rankings and improved research, made possible by the available data on customers’ previous behaviour.

Finally, an online marketplace can sometimes generate the superstar effect, with homogeneous customers all agreeing on which product is the best and buying it (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2019, p.8). In the case of apps, this phenomenon is extremely strengthened when software benefits from direct network effects and its utility largely depends on the size of the installed base (e.g. instant messaging apps). In these cases, the probability of being in presence of a tipping (or “winner-takes-all”) market is high.

Lower Replication Costs. In addition to being subject to marginal costs which are close to zero, software is a non-rival, meaning that it can be consumed by one person without reducing the amount of quality available to others, and, in absence of a legal or technological limit, non-excludable good, so it can be reproduced and used by anyone at approximately no cost. These characteristics often generate opportunities, like the possibility of implementing bundling strategies at a very low marginal cost, very common in the software industry, but also some threats.

Low replication costs and non-excludability are piracy’s main reasons for existence. Piracy has been a long-discussed issue in the software industry and illegally distributed copies actually offered in some ways opportunities for free sampling and strengthening network effects in the past, leading researchers and companies to think of piracy as an advantage under certain conditions. Raising the barriers of protection causes, in fact, some users to buy the product and others to live without it or look for alternatives, consequently reducing the installed base and its value also for those users that paid for the program (Reavis Conner and Rumelt, 1991, pp. 136-137). In addition, illegal copies contribute to raising switching costs for pirates, with a higher probability that they would later buy the software. Today, the incentive not to get in the way of illegal distribution has been partially revised, also considering the effectiveness of freemium software in covering the same functions previously fulfilled by piracy, while remaining in control of intellectual property and generating some earnings from advertising, for example (Halmenschlager and Waelbroeck, 2014, pp. 30-31; Nan et al., 2018, p. 283).

In some way, compatibility can be seen as a limit to software duplication: in fact, software needs to be compatible with other elements of the ecosystem (the operative system, in particular) and, therefore, in some cases, it cannot be run without some efforts by developers to make this possible. Sometimes, making software compatible with an additional OS can be almost as expensive as it was creating it at first and it needs some incentives from the platform owner side, such as, for example, a large installed base, a high-quality development toolkit or low monetary and technical entry barriers: developers that choose to target two or more ecosystems try to balance between a greater potential market and the cost of porting the product for different platforms (Hyrynsalmi et al., 2012, p. 60; Koch and Kerschbaum, 2014, pp. 1432-1434; Rochet and Tirole, 2003, pp. 1015-1017). Examining the strategy of the most popular apps, multi-homing might be assumed sometimes to be a viable way to increase the circulation of an app. However, the effect could be bi-directional and popularity in a single ecosystem could actually trigger the porting of the app in a second one. In fact, on mobile app stores, the large majority of apps (about 87 to 95 percent) are developed for a single technology platform and apparently, a multi-homing strategy isn’t very effective in making an app more popular than others (Ali et al., 2017, p. 5; Hyrynsalmi et al., 2012, p. 71). While at least professional developers would be expected to develop cross-platform apps, one out of five top-rated apps are not present on both Android and iOS, for reasons which reportedly are lack of resources, platform restrictions, low expected revenue in the other platform, user fragmentation within a platform and competition being already present, and, even if developed for both platforms, in any case, they are usually not consistently released in terms of new versions and updates (Ali et al., 2017, pp. 6-7). Obviously, if multi-homing can be hard for companies with skilled developers, it gets even rarer in an ecosystem that contains a good number of app publishers doing it just for fun or lacking a clear monetisation plan (Hyrynsalmi et al., 2012, p. 68). In addition to that, platforms in some industries tend not to promote multi-homing and even to obstacle it when it reduces possibilities of differentiation. While setting conditions that raise developer attractiveness usually increases the share of cross-platform software available, it also reduces user attractiveness when compared to other platforms (Hyrynsalmi et al., 2012, p. 70).

Lower Transportation Costs. The cost of transporting information goods over the Internet is quite near zero. Software has been distributed online and in physical formats for many years now and, while, back in the days, offline distribution was certainly more widespread, the Internet started to pick up as an important distribution channel soon.

Anyway, software distribution over the Internet used to present some drawbacks, in particular in the past. In fact, anyone could post software to the Internet, with no accountability and making malicious software downloads quite common, creating the need for a solution for trusted software distribution (Rubin, 1995, p.7). From a certain perspective, app stores answered to that problem, creating a trusted and secure channel even for less technologically advanced customers. In addition, they also provided a more efficient and faster system for automated software updates, making them almost unnoticeable to unaware customers, reducing security threats and improving user experience.

Today, when getting information on which app to download, users place their trust in app store owners, creating a way closer relationship with intermediaries than third-party software developers (Buck et al., 2014, p. 13).

Lower Tracking Costs. In a digital domain, user activity can be easily recorded and stored (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2019, p. 19), enabling relevant opportunities to make software selling more efficient. A major example of this is personalized recommendations, present on almost every online marketplace as well as on mobile app stores.

The availability of information on user behaviour also opened up new price discrimination opportunities: in particular, freemium, a specific kind of versioning, became predominant. Freemium, a combination of the words “free” and “premium”, is a business model by which a service or a product is offered free of charge, but a premium version is charged for advanced features, functionality, related products or services (Liu et al., 2014, pp. 327-328). Therefore, the free basic version of the product contains limited features, less privacy, more advertising or limited time usage (Boudreau et al., 2022, p. 1378). Freemium insert itself in a context of sampling and versioning strategies, that proved, for many years, to be efficient in creating a positive brand attitude and awareness when uncertainty about the product is high (Arora et al., 2017, p. 63). In addition to that, mobile applications are largely experience goods and it can be difficult for customers to quantify the true value of the product before using it, while a free version of the software allows customers to get to know the product, expecting that a considerable share will purchase the premium version (Boudreau et al., 2022, p. 1379). The freemium strategy in the app economy is also used to exploit advantages ascribed to positive network effects, product complementarity and an accelerated diffusion process. For companies leading the market, a free version of an app may provide a method for exploiting their advantage and expanding their lead over their competitors; for new entrants, a freemium strategy may provide a way to eat a part of the leader’s advantage (Boudreau et al., 2022, pp. 1375-1376). However, unlike traditional software, apps are generally characterized by minimal learning and switching costs and a low degree of interdependence among apps from the same developer (Liu et al., 2014, p. 330), raising fragmentation and competition. Implementing this strategy remains anyway quite complex and a trade-off emerges: on one side, consumers will judge the app on the basis of the quality of the free version (Liu et al., 2014, p. 330); on the other side, if the free app is sufficient for users, it could cannibalize the paid version.

Nevertheless, collecting users’ information isn’t always positive and privacy regulation puts a cost on tracking information flows (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2019, p. 23): on one hand, there are legal compliance costs and, on the other, there is a huge reputation risk. Many users report being very concerned about their privacy, but they still frequently download free apps that monetize their personal data, bringing to light a piracy paradox. Clearly, consumers on the Internet articulate their need for privacy, but they act in an opposite direction (Buck et al., 2014, p. 4).

Lower Verification Costs. As already discussed, mobile app stores, as two-sided platforms, contribute to increasing trust among participants through the rating system. In an offline setting, the company’s reputation rests on having an uninterrupted series of transactions with a positive outcome; online and on app stores in particular, the purchase is typically a one-time event, meaning that the reputation system becomes fundamental in providing insights on the app quality and making it public for users, in a way to discourage opportunistic behaviours of app developers, even if the transaction is often a unique event (Müller et al., 2011, p. 67).

Anyway, mobile apps are continuously evolving at a rapid pace with updates being released and replacing older versions quite frequently. As a result of app updates, user satisfaction may change frequently and traditional rating systems appear sometimes unable to capture these dynamics since they are usually resilient to average rating fluctuations when the app has already a substantial number of previous reviews. This system disadvantages new emerging developers, considering that initial low quality of the app and consequently low ratings may cause the impossibility to come back to a good average score later and it could encourage developers to release a new version of a badly reviewed app as a completely new one, trying to reset its reputation (Ruiz et al., 2015, p. 11).

Moreover, another problem of review systems on online marketplaces is “reputation inflation”. In fact, average public feedback scores on these platforms have greatly increased and it looks like customers are reluctant to give a low rating (in particular when the feedback is public) because they fear retaliation or they don’t want to harm the seller. In addition, the perceived cost of leaving a negative review increases higher the average rating, pressuring consumers to leave above-average scores (Filippas et al., 2018, p. 30; Horton and Golden, 2015, p. 2). In the long term, this phenomenon makes the reputation system less informative and also creates nonlinear rating expectations for buyers, raising the threshold above which buyers consider the average score a good one.

All in all, the advantages of mobile app stores as platforms and distribution channels are overwhelming, even if some aspects still need to be perfectly tuned. Their introduction contributed to making transaction costs, already decreased by digital economics, even lower and helped in democratizing software distribution.

Chapter 2. Literature Review

Many authors previously covered customer behaviour on online marketplaces, comparing it with the offline domain (e.g. Brynjolfsson and Smith, 2000; Brynjolfsson et al., 2003). Recently, literature also focused on user behaviour on mobile app stores: for example, Burghers et al. (2016, p. 330) argued how apps are generally low-priced or free and this causes low effort and regret when they are unsatisfied and decide to uninstall them. This means that the perceived risk in the buying decision process is low and leads, in many cases, to low involvement. In addition, some consumers appear to be unconscious and they do not seem to search for relevant information that could reduce the information asymmetries in the app market (Buck et al., 2014, p. 12). There is evidence that decision-making when dealing with app downloading often relies on heuristics (e.g. “take the first”), which allows users to quickly navigate across offerings, but may also cause customers to overlook some important information (Dogruel et al., 2015, p. 139).

In this context, it can be assumed that some elements in the presentation page of an app on a store may be effective in convincing a user to download it. In particular, three main references and their influence on user’s intention to download will be investigated below: app reputation, its popularity (and the consequent peer influence) and the developer’s brand.

Product reputation impact on purchase decisions online has already been covered by many authors. Chevalier and Mayzlin (2006, pp. 353-354), for example, proved that an improvement in online reviews is positively correlated with an increase in sales and the impact of ratings isn’t linear, with one-star reviews being more influential than five-star reviews. Moe and Trusov (2011, pp. 455-456) testified how ratings can improve sales, but customer rating behaviour is significantly socially influenced by previously posted ratings. Previous literature investigated eWOM (electronic word-of-mouth) valence, usually reflected by the average rating score, as well as eWOM volume, which is usually measured by the number of reviews. Out of the papers that covered eWOM valence on mobile app stores, seven of them were able to find a positive impact on app success (Böhm and Schreiber, 2014, p. 13; Burgers et al., 2016, p. 340; Chen et al., 2022, pp. 6-7; Finkelstein et al., 2017, p. 38; Gokgoz et al., 2021, pp. 434-435; Jung et al., 2012, p. 936; Lee and Raghu, 2014, p. 161), one found a negative correlation (Liang et al., 2015, pp. 250-251) and four found no significant impact (Roma and Ragaglia, 2016, pp. 184-185; Sällberg et al., 2022, pp. 7-10; Timmerman and Shepherd, 2016, pp. 14-15; Wang et al., 2015, p. 5). On the other side, four authors discovered a positive relation between app success and the number of reviews (Burgers et al., 2016, p. 340; Lee and Raghu, 2014, pp. 149-151; Sällberg et al., 2022, p. 13; Wang et al., 2015, pp. 7-10), while just one found out it was negative (Liang et al., 2015, pp. 250-251). The majority, in both cases, used the number of downloads in a selected time period as a performance metric, while some others preferred app survival in the top-apps lists. Overall, reputation in the mobile ecosystem has already been studied enough to take some preliminary conclusions and the majority of past literature contributions agree that reputation signals quality and it has a generally positive effect on sales.

The popularity of an app is reflected in multiple elements of an app store: firstly, the number of downloads is usually shown in the app page, then the top-list presence and app sales rank also signal it is popular among users (Sällberg et al., 2022, p. 3). Popularity translates into more interest among potential customers because it reflects the previous interest of other consumers and this peer influence has been shown to be one of the primary drivers of purchase decisions in online shopping (Liu et al., 2014, p. 330). Salganik et al. (2006, p. 855) have already shown how popularity information and social influence affect other users’ choices on music platforms, making popular songs even more popular. Also in the software industry, there is evidence that app popularity, reflected, for example, in the presence in top-apps ranking, has a positive impact on app success (e.g. Finkelstein et al., 2017, p. 2679). In addition, his effect may be even stronger in the case of software that generates strong network effects, since its utility increases with popularity and users are expected to consider that. Finally, the consequences of reputation aren’t independent of social influence: interestingly, less popular products in the market are more significantly influenced by online reviews (Liu et al., 2014, p. 331).

The third and last considered anchor is the brand of the company developing the app. Even if online marketplaces lower prices and reduce information asymmetries, brands remain sources of competitive advantage (e.g. Brynjolfsson and Smith, 2000, p. 580). In the mobile ecosystem, Roma and Ragaglia (2016, p. 184), for example, have already shown how a company’s fame positively moderates app success. On mobile app stores, the brand may be reflected in multiple elements of the presentation page: apart from the developer or publisher name, which is usually present, the company’s name is sometimes included also in the app’s name and in the icon. While, if taken singularly, each one of these elements has a relative importance on purchase decision which is low, at least if compared to average review rating and number of reviews (Böhm and Schreiber, 2014, p. 12), they could combine and consistently influence users. Furthermore, app icons are graphic elements and they are easy to understand for users (Böhm and Schreiber, 2014, p. 8) and Pol (2015, p. 51) showed how consumers prefer apps with a brand logo, well-known brands also gain an additional advantage and the brand attitude has a positive effect on the perceived app quality.

Chapter 3. Empirical Analysis

The experimental approach used in this research aims to understand how users’ intention to download (ITD) varies when three main variables (app reputation, popularity and developer fame) and their values change, taking also into consideration their interaction effects, the effect of comparison and of involvement in mobile apps, in the app purchase process and in the app category selected for the purpose of the experiment. Differently from previous research on the topic, this study focuses on direct user participation as its central characteristic: in fact, most of previous literature investigating the effect of the same variables used the number of downloads or an app survival in app store rankings as performance measures. However, while scraping mobile app stores as a method for data collection allows for larger samples, the algorithms behind app rankings on these stores are not public and their functioning is unknown, meaning they could not directly reflect users’ preferences. For example, Google’s Play Store top apps rank is probably based on a complicated algorithm, that takes into consideration multiple factors, such as app title, description, localization, retention rate, number of reviews, app updating, number of downloads and review ratings, meaning that a high rank does not always indicate a high user satisfaction (Liu et al., 2014, p. 348).

3.1 Method and Measurement

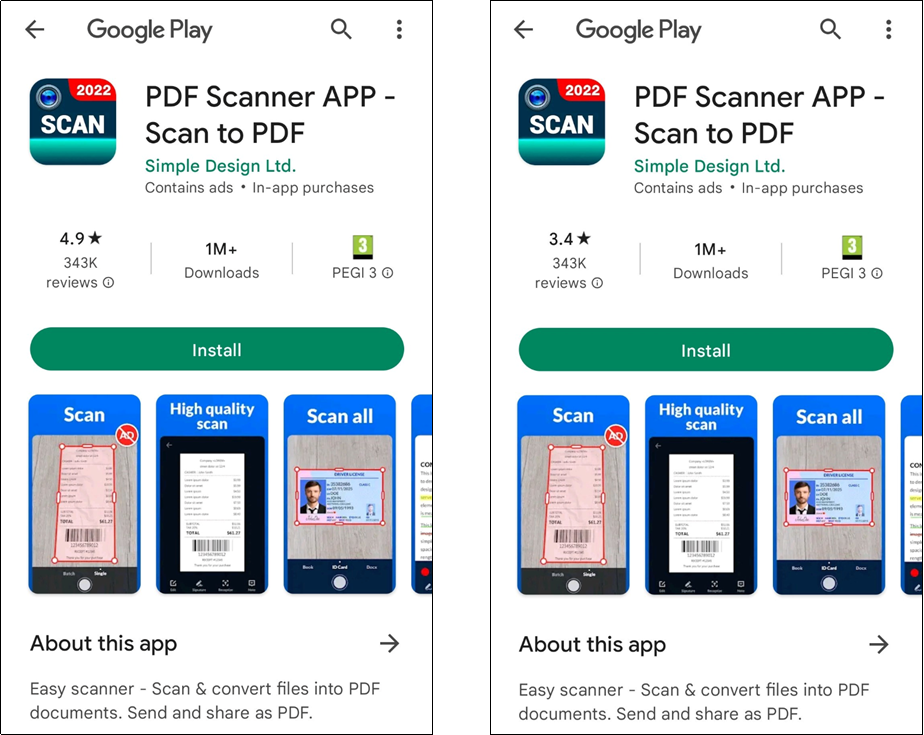

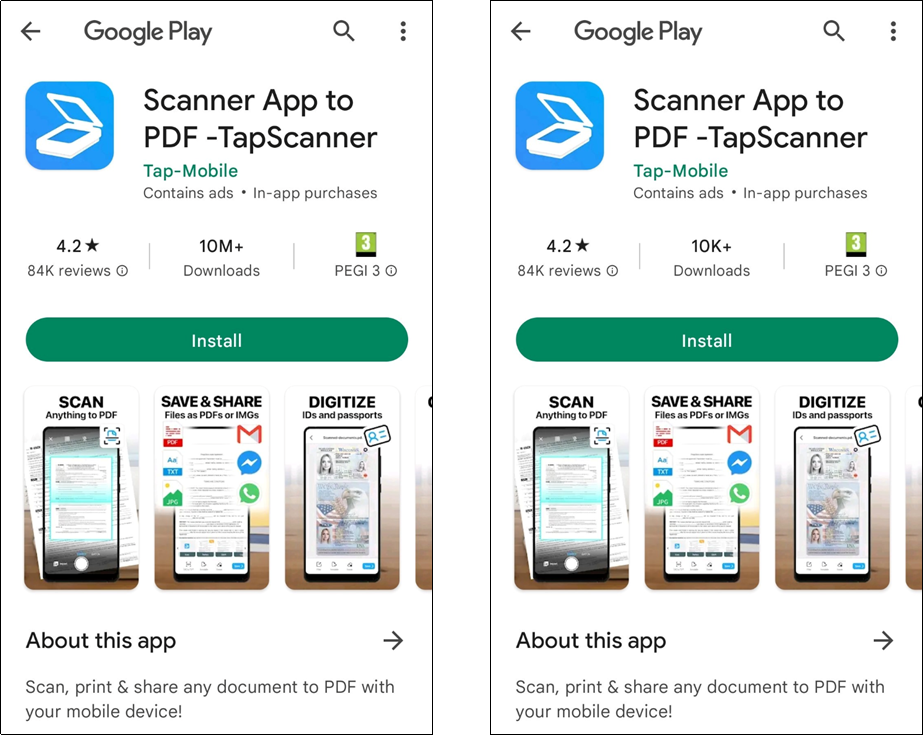

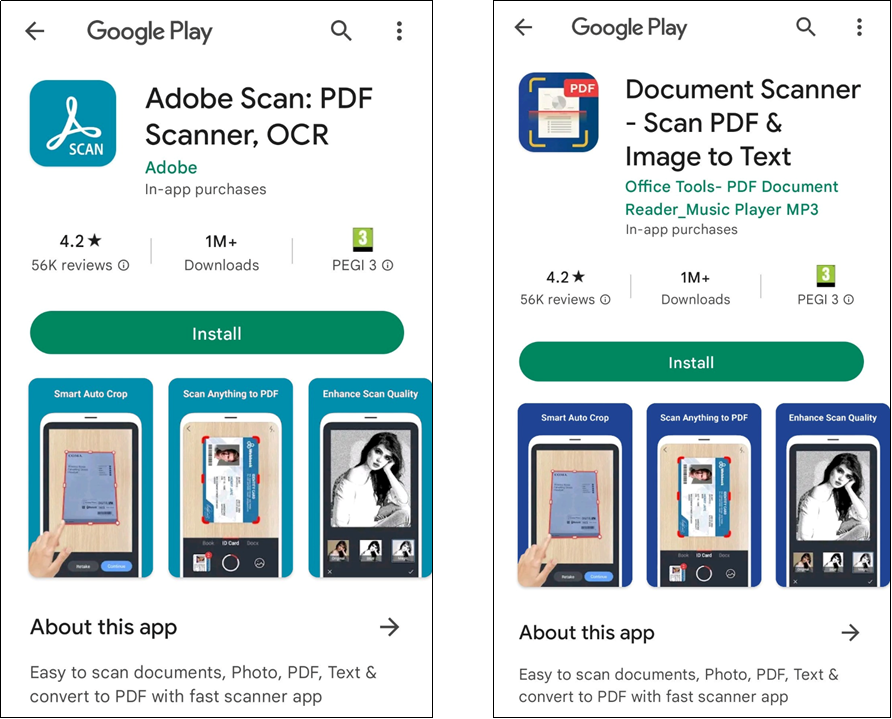

This research relies on an online questionnaire as its data source and the experimental design consists of parallel binary manipulations of the three main variables. For each one of these variables, one out of two manipulated screenshot images of the presentation page of some apps (presented in Appendix A) was shown to participants and their ITD was measured with a 7-point scale. Since intention can be defined as “the person’s motivation in the sense of his/her conscious plan to exert effort to carry out a behaviour” (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993, p. 168) or as “an individual’s conscious plan to make an effort to purchase a brand” (Spears and Singh, 2004, p. 56), intention to download is the person’s motivation in the consciously planning to make an effort to download an app (Pol, 2015, p. 18). The screenshots images were taken from Google’s Play Store, considering it is the most common app store on the most widespread mobile OS, which is Android, as shown in Fig. 1.1, and supposing that the majority of respondents would have been familiar with it.

Before being exposed to the manipulated variables, survey respondents were introduced to the questionnaire and asked some questions aimed to measure their involvement in apps as products (the online survey is integrally available in Appendix B). Firstly, their involvement in mobile apps in general and in the app download process were measured using Laurent and Kapferer’s scale, as presented in Mittal (1995, p. 670). Then, the involvement in the specific app category chosen for the experimental purpose was quantified through a reduced version, presented in Celuch and Taylor (1999, p. 120), of Zaichkowsky (1994, p. 70)’s involvement scale, which was already used for mobile apps in Kang et al. (2015, p. 213).

The app typology used in the experiment was mobile scanner apps, which allow to digitize physical documents through the smartphone camera and usually to export them in a digital format (e.g. PDF) in just a few seconds, and it was chosen for different reasons. Firstly, this category is quite fragmented, with many apps with small market shares, and the majority of the available options share similar basic features, with just a few exceptions (e.g. better OCR): in order to empirically prove this hypothesis, a preliminary analysis of the scanner apps segment on the Play Store (reported in Appendix C) was conducted and a sample of 24 apps was taken in consideration. Clearly, these apps are relatively easy to develop and there are low entry barriers for companies with the desire to enter this segment. Secondly, mobile scanner apps are subject to really low network effects, allowing to rule out the influence of network externalities and to measure the popularity variable effect by itself. Another important element was the presence in the category of an app developed by a company, Adobe, which is known worldwide for its software. Then, mobile scanner apps are non-hedonic apps and in this case review ratings become more important than ranks (Liu et al., 2014, p. 345). Furthermore, the fact that these apps act as still, at the moment, imperfect substitutes of traditional scanner machines may lead to think they are used by consumers with low involvement in the digitizing process, in line with the quick and impulsive buying setting described by Buck et al. (2014, p. 5), even if, since they belong to the productivity apps category, there is also evidence in the opposite direction (e.g. Sällberg et al., 2022, p. 10). Finally, the vast majority of these apps are offered with the freemium model, meaning that essential features are for free and, consequently, price is not a variable.

The order in which the three survey slides in which the app presentation pages of a mobile scanner app were included to measure users’ ITD was random and also which one out of the two screenshots corresponding to values of a variable was then randomly defined.

After these three slides, a manipulation check was also included, in a compromise (and not ideal) version designed to test the effectiveness of manipulations in the experimental design, but also not to give away the purpose of the data collection. Finally, the last slide included some measures of respondents’ demographics.

In conclusion, by conducting an analysis of variance and using three different regression models for each one of the three focal variables, the experiment aims to investigate their relation, together with the moderation of three involvement measures, with ITD. In addition, by comparing results from models across different variables, it is possible to determine which one is the most and the least effective variable. Finally, by introducing a variable that approximates comparison, the consequences of an app being shown as first or after other manipulated apps are investigated.

3.1.1 Variables

As anticipated, this research aims to determine how three variables, reflected in some elements of the app presentation page on mobile app stores, impact users’ choice to download an app. In this experimental design, app reputation, popularity and developer’s brand are included in form of three binary variables. In order to make these variables manipulation effective, it is necessary to define correctly the two values for each one of the binary variables.

Apart from the three main variables, also involvement measures are included in the analysis models: definitions for involvement variables are available in the variables summary in Table 3.1, as well as for the variable reflecting comparison of an app with others. Since ITD was measured after the exposure to each one of the three main independent variables, three corresponding dependent variables (also defined in Table 3.1) resulted from the data collection and they are separately used in different analysis models.

Table 3.1: Summary of all variables with definitions and descriptive statistics.

Note: this table is also available as an image.

| Variable | Definition | Descriptive Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Min | Max | ||

| Dependent Variables | |||||

| Measured ITD of the apps with manipulated reputation | 4.0468 | 1.7077 | 1 | 7 | |

| Measured ITD of apps with manipulated popularity | 4.5255 | 1.5675 | 1 | 7 | |

| Measured ITD of apps with manipulated developer’s brand | 4.9674 | 1.5863 | 1 | 7 | |

| Independent Variables | |||||

| Binary variable, app reputation in terms of average review ratings: high (=1) vs. low (=0) | 0.4847 | 0.4998 | 0 | 1 | |

| Binary variable, app popularity in terms of number of downloads: high (=1) vs. low (=0) | 0.5031 | 0.5000 | 0 | 1 | |

| Binary variable, developer’s brand strength and fame: strong (=1) vs. weak (=0) | 0.5214 | 0.4995 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mean-centered involvement measure inmobile apps (as product category) | 0 | 1.0523 | -3.6619 | 1.6715 | |

| Mean-centered involvement measure in the app download process | 0 | 1.2974 | -3.6933 | 2.0367 | |

| Mean-centered involvement measure in the experimental app category (mobile scanner apps) | 0 | 1.0629 | -3.4802 | 2.5198 | |

| Dummy variable, position in which i=rep, pop, brand was shown to users: first (=0) vs. second or third (=1) | 0.6667 | 0.4714 | 0 | 1 |

App Reputation. In this research, app reputation (rep) is defined in terms of the average review rating in the five-star scale currently used on the Play Store. Taking into consideration the dynamics that affect online review ratings, such as, for example, reputation inflation and the not linear impact of good and bad reviews, the threshold above which a review rating is considered to be high cannot be set at the middle of the scale. Indeed, similarly to Roma and Ragaglia (2016, p. 180), this limit was set at the four-star level. This decision was also supported by the preliminary analysis of mobile scanner apps (reported in Appendix C), which shows how the large majority of the most popular scanner apps on the Play Store have average ratings above 4.5 stars. As a consequence, an average rating of 4.9 stars was defined as a high app reputation, while a value of 3.4 was defined as low. In both cases, the number of reviews was set to the same medium-high level, in order to give credibility to the presented rating.

App Popularity. As already discussed, app popularity (pop) can be reflected in many elements on an app store. In this case, since the aim was to directly investigate the specific moment in which users take the download decision, the number of downloads was chosen as a metric, also considering it is presented in a spotlighted position in the app page. The number of downloads is presented on the Play Store in form of the last downloads threshold that the app achieved and overcame (e.g. 1M+, where M stands for million), consequently the issue consists in defining above which downloads bracket an app can be considered popular. Since the analysis in Appendix C already took into consideration only popular apps, a biased sample that drives upwards the average downloads number, and the mode out that group was 10M+, the decision was to set this level as a high app popularity. In contrast, the low app popularity level was set to 10K+ (where K means thousand).

Developer’s Brand. The developer’s brand (brand) affects multiple elements in the app presentation page (app icon, app name and developer’s name). In this experiment, a brand was defined as strong when it enjoyed worldwide fame, also outside the mobile ecosystem, and Adobe, which is the eighth largest software company in the world by revenue, with more than 16 billion in 2022 (Murphy and Contreras, 2022), perfectly fits the definition. On the other side, brands were considered weak when they included generic references to their products, without a strong brand identity (e.g. “Office Tools” or “Tools & Utilities Apps”).

3.1.2 Sample and Data Collection

In total 545 participants have taken part in the research questionnaire (available in Appendix B), while 491 of them completed it, with a completion rate of 90.09 percent, and, consequently, were included in the sample. The majority of respondents in the sample were between the 18 and 24 years old (59.27%), while the rest was between 25 and 34 (28.11%), between 35 and 44 (5.91%), between 45 and 54 (2.85%), over 55 (2.04%) or under 18 years old (1.83%). More often respondents were females (63.34%) and less frequently males (34.83%), non-binary people (0.81%) or preferred not to specify (1.02%). Regarding their occupation, students were the most common category (69.45%), followed by full-time (19.55%) and part-time employees (5.70%), self-employed workers (2.65%), unemployed (0.81%), pensioners (0.41%) and participants with other occupations (1.43%). Finally, in terms of education level, the majority in the sample had achieved a bachelor’s degree (38.70%), while others had a high school diploma (35.85%), a master’s degree (18.94%) or a doctorate (1.83%). Some participants didn’t conclude high school (2.85%) or undertook other educational paths (1.83%).

Overall, ITD was measured three times for each one of the 491 participants, for a total of 1473 combined values of yrep, ypop and ybrand.

3.1.3 Data Analysis

Since this data collection corresponds to a repeated measures experimental model, the first step consisted in running an analysis of variance (ANOVA) among the three levels of different groups of respondents from which we are trying to achieve some results. In favour of better describing the ANOVA and also the following models, it is necessary to define i, j, k = rep, pop, brand with i ≠ j ≠ k. Then, it is useful to redefine xi as xin and yi as yin, where n = 1, 2, 3 is the random position (first, second or third) in which users were exposed to the variable i. An ANOVA investigating variance across groups defined by different values on three levels (i, xi and n) that are supposed to affect each measure of yin may help in understanding if some effects on the dependent variable exist and where they come from.

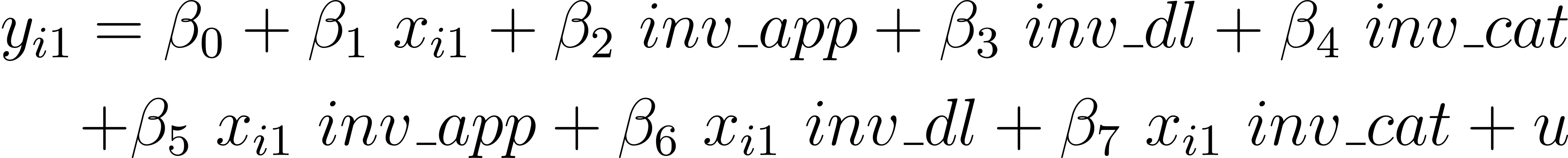

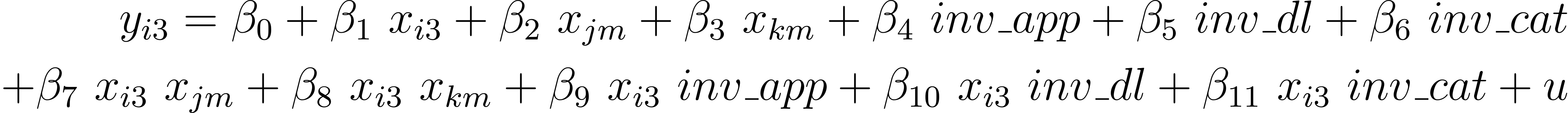

Thereafter, in order to derive more precise results, three different linear regression models were used for each one of the focal variables, to cover all possibilities and for a total of nine regressions. Now, the simplest regression model (Model 1) can be defined as:

where u is the error term. The data set used for Model 1 (M1) for i includes only observations in which respondents were exposed to i before j and k (n = 1), in a way that the resulting ITD cannot be biased by comparison with other apps. In addition, it allows to verify the moderating effects of various measures of involvement on the relationship between the focal predictor and ITD. This model is the main source of evidence for the effects of the focal independent variable xi and the role of involvement as moderator.

Then, Model 2 (M2) allows for two-way interactions also between different focal independent variables and takes into account only observations with n = 3, in the following way:

with m = 1, 2. The main objective of Model 2 is to explore whether there is any interaction between each couple of focal variables, reflecting comparison effects which depend on their alternatively high or low values.

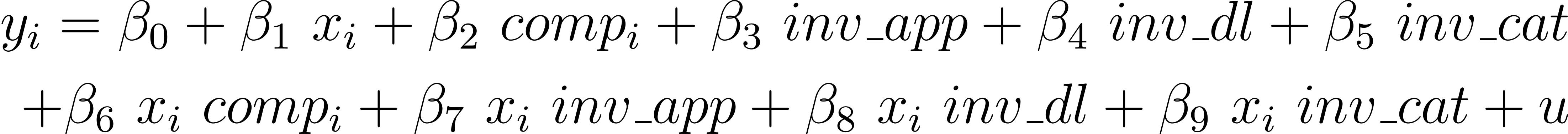

Finally, Model 3 (M3) can be defined considering all observations in the sample, independently from any specific value of n and introducing the compi variable and its interaction:

In the case of equation (3.3), differently from (3.1) and (3.2), n can take values which are not only 1 or 3, meaning that, while it allows to use a larger sample, it needs to include the compi variable (presented in Table 3.1), in order to take in account the possibility that results could be affected by comparison with xj and xk, which are not included in Model 3.

Concluding, after analyzing the preliminary results of the ANOVA, the comparison of coefficients resulting from models with the same value of i, together with the coefficient of compi from Model 3, helps to reach a further objective of this research, which consists in understanding how an approximation of comparison impacts the customer choice, while differences in coefficients from models depending concurrently on i, j or k could be explained by diverse effectiveness of app reputation, app popularity and brand.

3.2 Results

From the ANOVA emerges how variance is statistically significant across groups defined by different focal variables i (F(2, 4) = 42.187, p < 0.01), by different levels of xi (F(1, 4) = 60.841, p < 0.01) and by different presentation positions n (F(2, 4) = 2.369, p < 0.1), meaning that these three dimensions are likely to predict differences in the dependent variables yin. In addition, also the results regarding the three-way interaction i × xi × n are statistically significant (F(4) = 2.681, p < 0.05) and provide further foundations for subsequent analyses.

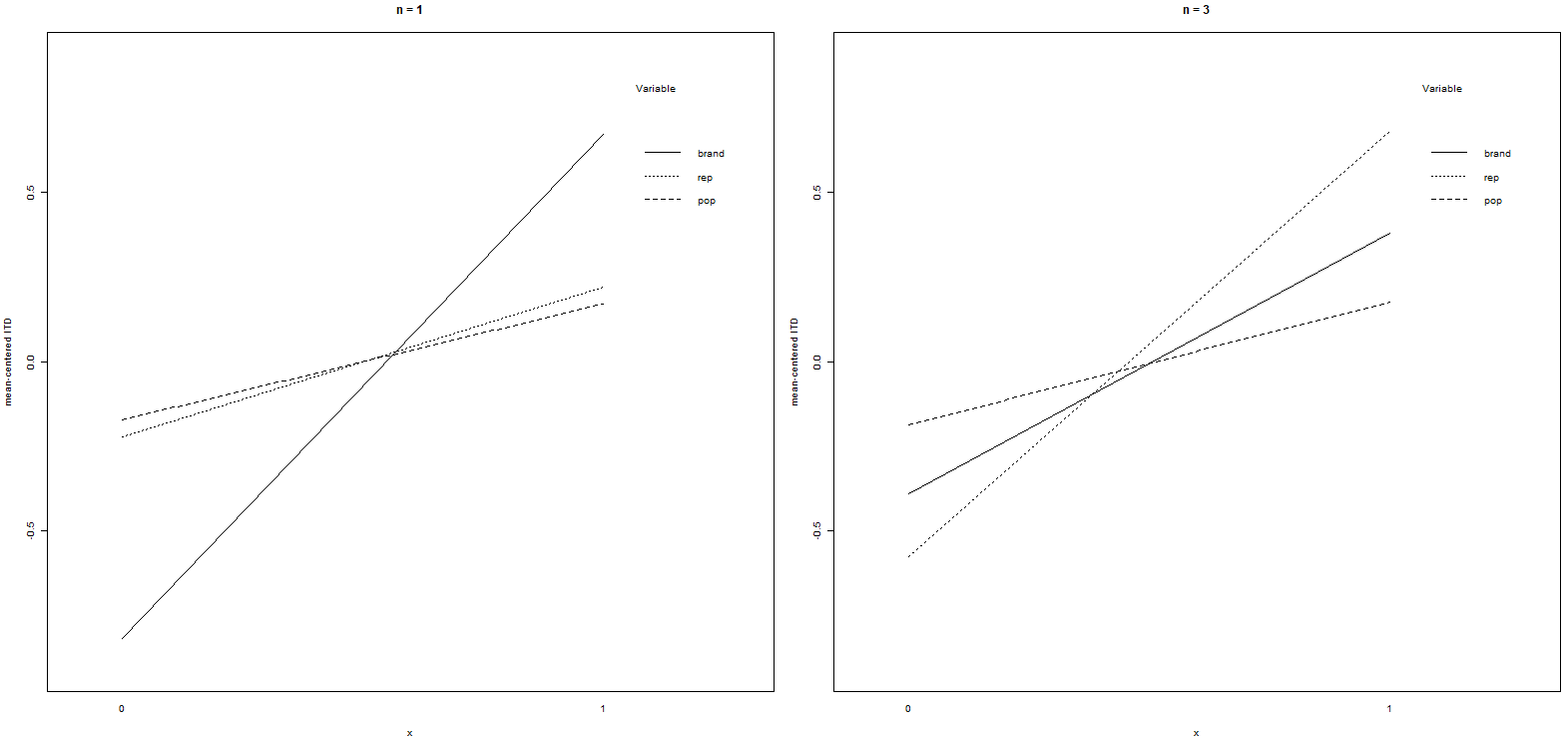

Then, the following step consisted of three different models and nine linear regressions. All information from these regressions, including R2 values and manipulation check ratios, are available in Table 3.2. Model 1 included in turn a focal variable (corresponding to different values of i) and involvement measures, together with their interaction terms. From the first model emerges how, when the app was shown as first (n = 1), the developer’s brand was the most effective in predicting ITD (β = 1.5289, p < 0.01), followed by reputation (β = 0.4986, p < 0.1) and popularity (β = 0.3611, p < 0.1). Regarding their interactions with involvement, a positive moderating effect of involvement in the download process on reputation was found (β = 0.3861, p < 0.1), a similar effect to the positive one operated by involvement in the specific app category on the developer’s brand (β = 0.4001, p < 0.1).

The ITD data included in Model 2 was measured after respondents were exposed to the third app (n = 3), which contained a manipulated value of a random one out of reputation, popularity and brand. The main aims of this model were to determine whether the selected focal variable could be moderated by the values of the other two to which users were previously exposed and also to verify if the effectiveness on ITD remained unchanged if compared to Model 1. In the results from Model 2, there was a reversal between the developer’s brand (β = 1.0347, p < 0.05) and reputation (β = 1.3351, p < 0.01), which became the most important element of the three, while the effect of popularity was statistically insignificant. No significant evidence of any moderation effect between one focal independent variable on the others surfaced, while there was evidence, confirmed also by Model 3, of a positive moderation of involvement in apps as generic products on all three focal variables xrep, xpop and xbrand.

Finally, regressions based on Model 3 included all observations, independently from the position in which apps were shown. The main objective was to investigate the moderating effect of the variable compi, while also confirming the levels of effectiveness of x_i, as derived from Model 1 and 2. Out of Model 3 emerged that, when accounting for all the observations (independently from n values), the developer’s brand was the best predictor of ITD (β = 1.5028, p < 0.01), followed by reputation (β = 0.4576, p < 0.1) and popularity (β = 0.3677, p < 0.1). Furthermore, there is evidence of a statistically relevant and negative moderating effect of comparison on brand effectiveness (β = -0.7454, p < 0.05) in predicting ITD.

Table 3.2: Resulting coefficients and standard errors of all regressions.

Note: this table is also available as an image.

| Model (i) | M1 (rep) | M1 (pop) | M1 (brand) | M2 (rep) | M2 (pop) | M2 (brand) | M3 (rep) | M3 (pop) | M3 (brand) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 3.86914*** (0.18683) | 4.63458*** (0.15161) | 4.13417*** (0.17373) | 3.69158*** (0.26951) | 4.14837*** (0.30527) | 4.341602*** (0.333232) | 3.906095*** (0.190949) | 4.64269*** (0.15454) | 4.118051*** (0.178167) |

| 0.49862* (0.26259) | 1.33507*** (0.41115) | 0.25362 (0.37742) | -0.285980 (0.360243) | 0.457599* (0.268971) | |||||

| 0.36110* (0.21478) | -0.21677 (0.31337) | 0.53397 (0.46800) | 0.406845 (0.363070) | 0.36773* (0.21838) | |||||

| 1.52889*** (0.23554) | -0.30136 (0.31366) | -0.18598 (0.37590) | 1.034683** (0.432264) | 1.502819*** (0.240948) | |||||

| 0.09502 (0.17658) | 0.3581** (0.16063) | 0.23275 (0.15521) | -0.01990 (0.15111) | -0.18401 (0.20203) | -0.188448 (0.183269) | -0.028741 (0.099168) | 0.10192 (0.09446) | 0.083030 (0.093585) | |

| -0.21222 (0.15674) | -0.2292* (0.1235) | -0.09778 (0.13349) | 0.04958 (0.11528) | -0.2527* (0.1505) | -0.034777 (0.139169) | 0.008458 (0.080334) | -0.16296** (0.07627) | -0.004562 (0.077751) | |

| 0.35115* (0.20204) | 0.22163 (0.14454) | -0.04189 (0.15636) | 0.12016 (0.14256) | 0.51847*** (0.19119) | 0.287315 (0.173767) | 0.106364 (0.099436) | 0.29048*** (0.09247) | 0.067097 (0.089394) | |

| -0.353854 (0.227152) | -0.28259 (0.19705) | 0.473583** (0.211797) | |||||||

| -0.74373 (0.53923) | 0.251013 (0.507205) | ||||||||

| -0.37078 (0.46066) | -0.676553 (0.511097) | ||||||||

| 0.16603 (0.46738) | 0.39159 (0.54648) | ||||||||

| 0.2172 (0.26755) | -0.0579 (0.23277) | 0.24104 (0.21184) | 0.28639 (0.22414) | 0.57307** (0.26890) | 0.540929** (0.260608) | 0.278238* (0.146581) | 0.29718** (0.13356) | 0.214755 (0.131852) | |

| 0.38614* (0.23255) | 0.10327 (0.16633) | -0.03326 (0.17832) | -0.14902 (0.17801) | 0.08568 (0.22437) | -0.071512 (0.193776) | -0.004344 (0.116336) | 0.00806 (0.10656) | -0.174237 (0.105738) | |

| -0.10643 (0.27486) | 0.06545 (0.20051) | 0.40013* (0.23065) | 0.18534 (0.21138) | -0.42987 (0.27914) | 0.006635 (0.253132) | 0.200011 (0.142551) | -0.11139 (0.13035) | 0.158655 (0.128399) | |

| 0.510013 (0.322484) | -0.39837 (0.27846) | -0.745391** (0.289854) | |||||||

| R2 | 0.09523 | 0.139 | 0.2885 | 0.1874 | 0.1417 | 0.1533 | 0.098 | 0.1056 | 0.1555 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.05031 | 0.1057 | 0.2542 | 0.1388 | 0.06958 | 0.08682 | 0.08112 | 0.08885 | 0.1397 |

| Observations (N) | 149 | 189 | 153 | 196 | 143 | 152 | 491 | 491 | 491 |

| Manipulation Check (%) | 75.84 | 62.43 | 68.63 | 79.08 | 55.94 | 63.16 | 77.19 | 60.49 | 67.41 |

| ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1 |

3.3 Discussion and Managerial Implications

The results indicate that the developer’s brand is generally the most effective factor in determining dl decision if compared to reputation (review ratings) and popularity (number of dls), but effectiveness varies on presentation order and information available to users (M1, M3). An unexpected outcome is the scarce (and almost zero) effectiveness of popularity, even if this setting had very low network effects. A hypothesis on the reason why popularity is not frequently taken into consideration by users may rest in the necessity for platform owners (as Google, in this case) to keep the ecosystem competitive and attractive for new developers, avoiding single-firm dominated markets and preserving information transparency on the platform (Boudreau et al., 2022, p. 1379), in particular when network effects are present: in fact, the format in which quantity of downloads is presented (e.g. 10M+ vs. 10K+) may be intentionally not very powerful in communicating the magnitude of popularity differences across apps and it may go unnoticed when users are not reviewing information carefully.

The high effectiveness of brands in shaping users’ choices, even in an online market where a wide range of information is available, opens up relevant opportunities for established software companies. In fact, developing different apps, covering many different segments, already proved to be a successful strategy, since Lee and Raghu (2012, p. 161) pointed out how diversifying app portfolios across selling categories is a key determinant of sales performance.

When users are exposed to information about multiple apps and they can consequently compare them, reputation becomes the most effective element (M2), as also shown by the parallel in Fig. 3.1 between ITD for apps shown as first (n = 1) and those shown as third (n = 3). Users may rely more on eWOM when they have the possibility to consider a wider range of options and they just may need some anchors to better understand apps’ rating levels. An important cue for making an informed decision can be often found in past experience, but, when users have no previous experience with the specific product, they often rely on social experiences, as expressed in reviews (Burgers et al., 2016, p. 329). As a consequence, it is important, in particular for new entrants in an app category that are not likely to be shown in top search results, to publish an app when it is mature enough to avoid the common phenomenon of reputation backlash, in terms of initial low ratings. On the other side, brands become less predictive of ITD when comparison is introduced in the model (as evidenced by the coefficient of compi in M3): a popular brand may combine well with the “take the first” heuristic, which has already proven to be effective in the case of mobile apps (Dogruel et al., 2015, p. 139), and be penalised when users are actively collecting information.

Figure 3.1: Mean-centered ITD (yi) depending on high vs. low values (x) of developer’s brand, reputation and popularity, with n = 1 and n = 3.

Some other interesting evidence regards the moderation effects of involvement on the three focal variables. First, there is predictable and generalized evidence that higher involvement in apps as products corresponds to a higher effectiveness of all three reputation, popularity and brand levels in driving users’ ITD (M2, M3). Second, when users are highly involved in the app download process, they tend to rely more on reputation, probably because they scrutinise information more closely. Last, when the involvement in the specific app category (mobile scanner apps, in this case) is high and users consequently perceive a higher risk in the app choice, also considering that scanner apps are productivity apps, frequently used for work (Sällberg et al., 2022, p. 10), they appear to preferably choose a strong and known brand (M1), which is a commonly used as a cue when attempting to mitigate it (Matzler et al., 2008, p. 158).

3.4 Limitations

This experimental approach presents some limitations. The first and major limitation lies in the experimental design: in fact, while investigating the effect of three factors on ITD, the selected one was not a traditional three-way factorial design and just one variable was manipulated at each measurement of ITD, while, at the same time, the others were set to intermediate values. As a consequence, estimates of interactions among factors were not ideal, but, on the other side, it allowed to effectively collect results on comparison effects. Consequently, despite the repeated measure design, it was not possible to include all observations of yi in each sample used for each regression, since every measure of ITD was strictly related to a manipulated value of reputation, popularity or developer’s brand (i) happening in the specific case.

Some other limitations lie in the data collection. For example, the screenshot images used in the questionnaire were all collected from Google Play Store, the most used app store, meaning that users of other platforms, for example, Apple iOS, could be used to a different interface and to look for elements in other positions, affecting, therefore, the resulting ITD. In addition, some people, such as those with high levels of involvement, for example, may find limiting the experimental setting, in which many important elements were not considered or even included.

Finally, the sample may represent a limitation. In fact, the large majority of respondents were students and they were aged between 18 and 24 and results could be biased by this unequal balance of composition. Nowadays, smartphones are widespread across all customer age groups, but this doesn’t mean that these groups all share the same levels of involvement and rely on the same factors when making decisions that concern downloading an app or not. Additionally, while this is not certain, participants can be assumed to be mainly from Germany and Italy and there is some evidence that behaviour on app stores and factors relevant to the purchase decision vary across countries (Kübler et al., 2018, p. 37), meaning that results may vary depending on sample geographical origin and cultural background.

Chapter 4. Conclusion

4.1 Summary

As a first step, in Chapter 1, an extensive background on the mobile ecosystem, its participants and its dynamics was provided, before reviewing, in Chapter 2, previous literature on user behaviour and determinants of downloads on mobile app stores. Finally, in Chapter 3, the empirical approach of this research was discussed, together with its results. The outcome of this experiment shows how the developer’s brand is generally the most decisive element, but, when a comparison between apps is introduced in the model, it loses its effectiveness and reputation becomes more relevant. Popularity and peer influence, in the context of low network effects, appear to be unexpectedly ineffective in driving users’ decisions across all models. Moreover, users’ involvement in the download process reinforces the effect of reputation, while, when customers are more involved in the specific app category and perceive a higher risk, apps from established brands are more likely to benefit. Finally, it was not possible to find clear evidence of any two-way interaction between reputation, popularity and brand.

4.2 Future Directions

This research results add up to the substantial literature that already covered customer behaviour on online marketplaces, but some elements remain unexplored. For example, a better experimental design aimed to explore factorial interactions should be developed. Furthermore, peer influence effectiveness and its dynamics on app stores, both in the presence and absence of network effects, should be better investigated.

Bibliography

Ali, M., Joorabchi, M. E., & Mesbah, A. (2017). Same app, different app stores: A comparative study. In 2017 IEEE/ACM 4th International Conference on Mobile Software Engineering and Systems (MOBILESoft) (pp. 79-90), IEEE.

Anderson, C. (2006). The long tail: Why the future of business is selling less of more. Hachette UK.

Arora, S., Ter Hofstede, F., & Mahajan, V. (2017). The implications of offering free versions for the performance of paid mobile apps. Journal of Marketing, 81(6), 62-78.

Basole, R. C., & Karla, J. (2012). Value transformation in the mobile service ecosystem: A study of app store emergence and growth. Service Science, 4(1), 24-41.

Böhm, S., & Schreiber, S. (2014). Mobile App Marketing: A Conjoint-based Analysis on the Importance of App Store Elements. In CENTRIC 2014: The Seventh International Conference on Advances in Human-oriented and Personalized Mechanisms, Technologies, and Services.

Boudreau, K. J., Jeppesen, L. B., & Miric, M. (2022). Competing on freemium: Digital competition with network effects. Strategic Management Journal, 43(7), 1374-1401.

Brynjolfsson, E., Hu, Y., & Smith, M. D. (2003). Consumer surplus in the digital economy: Estimating the value of increased product variety at online booksellers. Management science, 49(11), 1580-1596.

Brynjolfsson, E., & Smith, M. D. (2000). Frictionless commerce? A comparison of Internet and conventional retailers. Management science, 46(4), 563-585.

Buck, C., Horbel, C., Germelmann, C. C., & Eymann, T. (2014). The Unconscious App Consumer: Discovering and Comparing the Information-seeking Patterns among Mobile Application Consumers. In ECIS.

Burgers, C., Eden, A., de Jong, R., & Buningh, S. (2016). Rousing reviews and instigative images: The impact of online reviews and visual design characteristics on app downloads. Mobile Media & Communication, 4(3), 327-346.

Ceci, L. (2022). Google Play: annual consumer spending on mobile apps 2016-2021. Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/444476/google-play-annual-revenue/ (Accessed in January 2023).

Ceci, L. (2022). Number of apps available in leading app stores Q3 2022. Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/ (Accessed in January 2023).

Celuch, K. G., & Taylor, S. A. (1999). Involvement with services: An empirical replication and extension of Zaichkowsky’s personal involvement inventory. The Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 12, 109-122.

Chen, H., Lachaud, K., & Zhou, W. (2022). The sales effect of “Free App of the Day” on Amazon Appstore: An empirical study. Digital Business, 2(2), 100020.

Chevalier, J. A., & Mayzlin, D. (2006). The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. Journal of marketing research, 43(3), 345-354.

Cortimiglia, M. N., Ghezzi, A., & Renga, F. (2011). Mobile applications and their delivery platforms. IT Professional, 13(5), 51-56.

Dogruel, L., Joeckel, S., & Bowman, N. D. (2015). Choosing the right app: An exploratory perspective on heuristic decision processes for smartphone app selection. Mobile Media & Communication, 3(1), 125-144.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt brace Jovanovich college publishers.

Ericsson (2022). Ericsson Mobility Report, https://www.ericsson.com/en/reports-and-papers/mobility-report/reports/november-2022 (Accessed in January 2023).

Filippas, A., Horton, J. J., & Golden, J. (2018). Reputation inflation. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference on Economics and Computation (pp. 483-484).

Finkelstein, A., Harman, M., Jia, Y., Martin, W., Sarro, F., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Investigating the relationship between price, rating, and popularity in the Blackberry World App Store. Information and Software Technology, 87, 119-139.

Friedman L. (2013). The App Store turns five: A look back and forward. Macworld, https://www.macworld.com/article/221393/the-app-store-turns-five-a-look-back-and-forward.html (Accessed in January 2023).

Gokgoz, Z. A., Ataman, M. B., & van Bruggen, G. H. (2021). There’s an app for that! Understanding the drivers of mobile application downloads. Journal of Business Research, 123, 423-437.

Goldfarb, A., & Tucker, C. (2019). Digital economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 57(1), 3-43.

Halmenschlager, C., & Waelbroeck, P. (2014). Fighting free with free: Freemium vs. piracy. Piracy (November 29, 2014).

Horton, J., & Golden, J. (2015). Reputation inflation in an online marketplace. New York I, 1.

Hyrynsalmi, S., Mäkilä, T., Järvi, A., Suominen, A., Seppänen, M., & Knuutila, T. (2012). App store, marketplace, play! an analysis of multi-homing in mobile software ecosystems. Jansen, Slinger, 59-72.

Ihlwan, M. (2007). LG ties up with PRADA for new phone. Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2007-01-17/lg-ties-up-with-prada-for-new-phone (Accessed in January 2023).

Jung, E. Y., Baek, C., & Lee, J. D. (2012). Product survival analysis for the App Store. Marketing Letters, 23(4), 929-941.

Kang, J. Y. M., Mun, J. M., & Johnson, K. K. (2015). In-store mobile usage: Downloading and usage intention toward mobile location-based retail apps. Computers in Human Behavior, 46, 210-217.

Koch, S., & Kerschbaum, M. (2014). Joining a smartphone ecosystem: Application developers’ motivations and decision criteria. Information and Software Technology, 56(11), 1423-1435.

Kouris, I., & Piller, F. T. (2014). App platforms as two-sided markets: analysis and modeling of application distribution platforms for mobile devices. Lehrstuhl für Betriebswirtschaftslehre, insbesondere Technologie-und Innovationsmanagement.

Kübler, R., Pauwels, K., Yildirim, G., & Fandrich, T. (2018). App popularity: Where in the world are consumers most sensitive to price and user ratings?. Journal of Marketing, 82(5), 20-44.

Lambrecht, A., Goldfarb, A., Bonatti, A., Ghose, A., Goldstein, D. G., Lewis, R., Rao, A. and Sahni, N. & Yao, S. (2014). How do firms make money selling digital goods online?. Marketing Letters, 25(3), 331-341.

Laricchia, F. (2022). Market share of mobile operating systems worldwide 2009-2022. Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/272698/global-market-share-held-by-mobile-operating-systems-since-2009/ (Accessed in January 2023).

Lee, G., & Raghu, T. S. (2014). Determinants of mobile apps’ success: Evidence from the app store market. Journal of Management Information Systems, 31(2), 133-170.

Liang, T. P., Li, X., Yang, C. T., & Wang, M. (2015). What in consumer reviews affects the sales of mobile apps: A multifacet sentiment analysis approach. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 20(2), 236-260.

Liu, C. Z., Au, Y. A., & Choi, H. S. (2014). Effects of freemium strategy in the mobile app market: An empirical study of google play. Journal of management information systems, 31(3), 326-354.

Matzler, K., Grabner‐Kräuter, S., & Bidmon, S. (2008). Risk aversion and brand loyalty: the mediating role of brand trust and brand affect. Journal of product & brand management, 17(3), 154-162.

Mittal, B. (1995). A comparative analysis of four scales of consumer involvement. Psychology & marketing, 12(7), 663-682.

Moe, W. W., & Trusov, M. (2011). The value of social dynamics in online product ratings forums. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(3), 444-456.

Müller, R. M., Kijl, B., & Martens, J. K. (2011). A comparison of inter-organizational business models of mobile app stores: There is more than open vs. closed. Journal of theoretical and applied electronic commerce research, 6(2), 63-76.

Murphy A., & Contreras I. (2022). The Global 2000. Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/lists/global2000/ (Accessed in January 2023).

Nan, G., Wu, D., Li, M., & Tan, Y. (2018). Optimal Freemium Strategy for Information Goods in the Presence of Piracy. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 19(4), 266-305.

Piccoli, G., & Pigni, F. (2019). Information Systems for Managers With Cases, Edition 4.0. Prospect Press, Inc..

Pol, M. (2015). App icon preferences: The influence of app icon design and involvement on quality and intention to download. Master’s thesis, University of Twente.

Reavis Conner, K., & Rumelt, R. P. (1991). Software piracy: An analysis of protection strategies. Management science, 37(2), 125-139

Rochet, J. C., & Tirole, J. (2003). Platform competition in two-sided markets. Journal of the european economic association, 1(4), 990-1029.

Roma, P., & Ragaglia, D. (2016). Revenue models, in-app purchase, and the app performance: Evidence from Apple’s App Store and Google Play. Electronic commerce research and applications, 17, 173-190.

Rubin, A. D. (1995). Trusted distribution of software over the Internet. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Network and Distributed System Security (pp. 47-53), IEEE.

Ruiz, I. J. M., Nagappan, M., Adams, B., Berger, T., Dienst, S., & Hassan, A. E. (2015). Examining the rating system used in mobile-app stores. Ieee Software, 33(6), 86-92.

Salganik, M. J., Dodds, P. S., & Watts, D. J. (2006). Experimental study of inequality and unpredictability in an artificial cultural market. science, 311(5762), 854-856.

Sällberg, H., Wang, S., & Numminen, E. (2022). The combinatory role of online ratings and reviews in mobile app downloads: an empirical investigation of gaming and productivity apps from their initial app store launch. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 1-17.

Spears, N., & Singh, S. N. (2004). Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. Journal of current issues & research in advertising, 26 (2), 53-66.

Timmerman, J. E., & Shepherd, I. (2016). Does eWOM affect demand for mobile device applications?. Journal of Marketing Development & Competitiveness, 10(3).

Wang, Y., Song, J., & Aguirre-Urreta, M. (2015). An empirical investigation of factors impacting application downloads in mobile app stores. SIGHCI Proceedings, 1-5.

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1994). The personal involvement inventory: Reduction, revision, and application to advertising. Journal of advertising, 23(4), 59-70.

Zheng, P., & Ni, L. (2010). Smart phone and next generation mobile computing. Elsevier.

Appendices

A App Page Screenshots